One Identity, Multiple Belongings

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- Civics & Citizenship

- History

- Social Studies

- Human & Civil Rights

- The Holocaust

Amin Maalouf, a writer who was born in Lebanon and immigrated to France, resists other people’s attempts to oversimplify his identity. He explains:

Since I left Lebanon in 1976 to establish myself in France, I have been asked many times, with the best intentions in the world, if I felt more French or more Lebanese. I always give the same answer: “Both.” Not in an attempt to be fair or balanced but because if I gave another answer I would be lying. This is why I am myself and not another, at the edge of two countries, two or three languages and several cultural traditions. This is precisely what determines my identity. Would I be more authentic if I cut off a part of myself?

To those who ask, I explain with patience that I was born in Lebanon, lived there until the age of 27, that Arabic is my first language and I discovered Dickens, Dumas and “Gulliver’s Travels” in the Arabic translation, and I felt happy for the first time as a child in my village in the mountains, the village of my ancestors where I heard some of the stories that would help me later write my novels. How could I forget all of this? How could I untie myself from it? But on another side, I have lived on the French soil for 22 years, I drink its water and wine, my hands caress its old stones everyday, I write my books in French and France could never again be a foreign country.

Half French and half Lebanese, then? Not at all! The identity cannot be compartmentalized; it cannot be split in halves or thirds, nor have any clearly defined set of boundaries. I do not have several identities, I only have one, made of all the elements that have shaped its unique proportions.

Sometimes, when I have finished explaining in detail why I fully claim all of my elements, someone comes up to me and whispers in a friendly way: “You were right to say all this, but deep inside of yourself, what do you really feel you are?”

Is there a danger in making people choose one part of their identity over others?

This question made me smile for a long time. Today, it no longer does. It reveals to me a dangerous and common attitude men have. When I am asked who I am “deep inside of myself,” it means there is, deep inside each one of us, one “belonging” that matters, our profound truth, in a way, our “essence” that is determined once and for all at our birth and never changes. As for the rest, all of the rest—the path of a free man, the beliefs he acquires, his preferences, his own sensitivity, his affinities, his life—all these things do not count. And when we push our contemporaries to state their identity, which we do very often these days, we are asking them to search deep inside of themselves for this so-called fundamental belonging, that is often religious, nationalistic, racial or ethnic and to boast it, even to a point of provocation.

Whoever claims a more complex identity becomes marginalized. A young man born in France of Algerian parents is obviously part of two cultures and should be able to assume both. I said both to be clear, but the components of his personality are numerous. The language, the beliefs, the lifestyle, the relation with the family, the artistic and culinary taste, the influences—French, European, Occidental—blend in him with other influences—Arabic, Berber, African, Muslim. This could be an enriching and fertile experience if the young man feels free to live it fully, if he is encouraged to take upon himself his diversity; on the other side, his route can be traumatic if each time he claims he is French, some look at him as a traitor or a renegade, and also if each time he emphasizes his links with Algeria, its history, its culture, he feels a lack of understanding, mistrust or hostility.

The situation is even more delicate on the other side of the Rhine. Thinking about a Turk born almost 30 years ago near Frankfurt, and who has always lived in Germany, and who speaks and writes the German language better than the language of his Fathers. To his adopted society, he is not German, to his society of birth, he is no longer really Turkish. Common sense dictates that he could claim to belong to both cultures. But nothing in the law or in the mentality of either allows him to assume in harmony his combined identity.

I mentioned the two first examples that come to my mind. I could have mentioned many others. The case of a person born in Belgrade from a Serb mother and a Croatian father. Or a Hutu woman married to a Tutsi. Or an American that has a black father and a Jewish mother.

Some people could think these examples unique. To be honest, I don’t think so. These few cases are not the only ones to have a complex identity. Multiple opposed “belongings” meet in each man and push him to deal with heartbreaking choices. For some, this is simply obvious at first sight; for others, one must look more closely.

If . . . people cannot live their multiple belongings, if they constantly have to choose between one side or the other, if they are ordered to get back to their tribe, we have the right to be worried about the basic way the world functions.

“Have to choose,” “ordered to get back,” I was saying. By whom? Not only by fanatics and xenophobes of all sides, but by you and me, each one of us. Precisely because these habits of thinking are deeply rooted in all of us, because of this narrow, exclusive, bigoted, simplified conception that reduces the whole identity to a single belonging declared with rage.

I feel like screaming aloud: This is how you “manufacture” slaughterers! 1

- 1Amin Maalouf, “Deadly Identities,” trans. Brigitte Caland, Al Jadid 4, no. 25 (Fall 1998), accessed July 12, 2007. Reproduced by permission from Al Jadid.

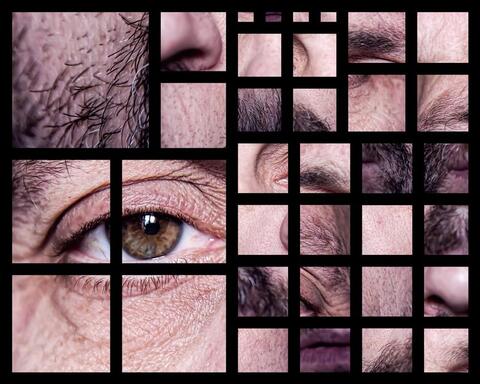

Fragmented images of a human face.

Connection Questions

- Amin Maalouf writes, “Multiple opposed ‘belongings’ meet in each man and push him to deal with heartbreaking choices.” What are some of the “heartbreaking choices” that he is describing? Can you add any examples from your own knowledge or experience?

- What does Maalouf believe is the danger in making people choose one part of their identity over another?

- This reading is an excerpt from an essay that Maalouf titled “Deadly Identities.” Why does he suggest that identities can be dangerous?

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "One Identity, Multiple Belongings," last updated August 2, 2016.