Transcending Single Stories

Overview

About This Lesson

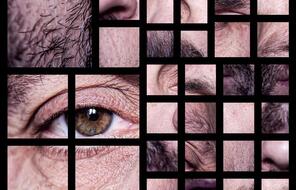

In the previous lesson, students grappled with the question “Who am I?” and then created visual representations of their own identities that captured how they view themselves and how others view them. In this two-period lesson, students will continue to explore the relationship between the individual and society by examining how we often believe “single stories” and stereotypes about groups of people. After analysing a Gary Trudeau cartoon. Street Calculus, that depicts the ways we often categorise strangers in the first class period, students will spend the second class period watching Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s thought-provoking TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story. Then, in the activities that follow, students will reflect on the human tendency of applying categories to the people and things we meet.

Trudeau and Adichie provide a framework for discussing the relationship between stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination with your students. A stereotype is a belief about an individual based on the real or imagined characteristics of a group to which that individual belongs. Adichie provides examples from her life that help illustrate how stereotypes can lead us to judge an individual or group negatively. Even stereotypes that seem to portray a group positively reduce individuals to categories and tell an incomplete or inaccurate “single story.” Prejudice occurs when we form an opinion about an individual or a group based on a negative stereotype. When a prejudice leads us to treat an individual or group negatively, discrimination occurs. It is important to provide students with opportunities to reflect on the relationship between the ways that we think about others and the ways that we treat others. Investigating the connections between stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination provides an important framework for exploring, in future lessons, the ways that people create “in” groups and “out” groups and the dangerous consequences these groupings can have when they are rooted in “single stories” rather than a more complete and nuanced narrative.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plans

Day 1 Activities

Day 2 Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Transcending Single Stories

Understanding Identity

Why Little Things Are Big

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand