This lesson examines the challenges Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael faced as they worked to translate the legal and legislative victories in the 1950s and early 1960s to social and economic policies and assume greater control over their lives and communities. Their efforts would expand the reach of American democracy and inspire other minorities to fight for recognition and influence. Despite their legal and constitutional successes, Black Americans continued to be subjected to discrimination and terror as they attempted to live out their constitutionally guaranteed rights. Frustrated with the slow pace of change, some Black Americans questioned many of the key assumptions of the civil rights movement, including the need for integration with the white community and the role of nonviolence in the freedom struggle.

Drawing inspiration from both his Christian faith and the peaceful teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. King led a nonviolent movement in the late 1950s and ‘60s to achieve legal equality for African Americans in the United States. While others were advocating for freedom by “any means necessary,” including violence, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. used the power of words and acts of nonviolent resistance, such as protests, grassroots organizing, and civil disobedience to achieve seemingly impossible goals. He went on to lead similar campaigns against poverty and international conflict, always maintaining fidelity to his principles that men and women everywhere, regardless of color or creed, are equal members of the human family. Dr. King’s less than thirteen years of nonviolent leadership ended abruptly and tragically on April 4th, 1968, when he was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee.

Malcolm X’s views challenged Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent tradition of the civil rights movement. Born Malcolm Little in 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, he grew up in Michigan, Boston, and New York. As a young adult, Little became involved in a life of crime and violence for which he was jailed for several years. While in prison he joined the Nation of Islam

and changed his name to Malcolm X. Under the leadership of Elijah Muhammad, the Nation of Islam made inroads into Black communities in the urban North by advocating a program of self-help, Black separatism, and Black nationalism. In the 1950s, the Nation of Islam grew in popularity in these communities and began to challenge long held beliefs in integration and reconciliation. Malcolm X challenged advocates of nonviolence and declared that Blacks could not be expected to respond nonviolently when attacked. He was shot and killed while speaking in New York City on February, 21, 1965.

Black nationalism and the militancy of Malcolm X appealed to members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

, many of whom had been beaten and terrorized by segregationists. After the march from Selma to Montgomery, SNCC targeted one of the poorest communities of Alabama—Lowndes County, where Blacks constituted 80 percent of the population and as of 1965 not a single Black person was registered to vote. Testing federal enforcement of the new Voting Rights Act, local farmer John Hulett, with the help of SNCC activists, founded the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). The LCFO was conceived as an independent political party whose goal was to offer an alternative to the Alabama Democratic Party, which continued to block Black voter participation. Seeking an image to represent the party, LCFO members adopted the Black panther as their symbol. Despite harassment and threats of violence, LCFO had registered 2000 new Black voters by the spring of 1966. Following the Lowndes County campaign, Stokely Carmichael replaced John Lewis as chairman of SNCC. Carmichael’s new, militant vision of Black nationalism changed the tone and direction of SNCC.

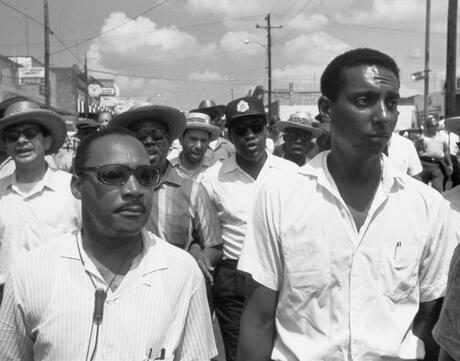

Stokely Carmichael and Dr. King were two of the civil rights leaders who joined James Meredith’s “March Against Fear” in June 1966. Meredith, the first Black American to enroll at the previously all-white University of Mississippi, had set out on a 200-mile march from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. Meredith hoped his example would encourage Blacks to stand up against intimidation and to register to vote. On the second day of his march, Meredith was shot and wounded. Leaders from all the major civil rights organizations came to Mississippi to continue the march, register voters, and protest the violent backlash against the civil rights struggle. Along the route, conflicts over strategy between King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and SNCC rose to the surface. Those tensions—over white participation and the efficacy of nonviolence—became public at a rally in Greenwood, Mississippi. Challenging the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., and the SCLC, Carmichael announced the arrival of the Black power movement, which signaled a change in the civil rights movement as Black Americans called for increased power and control over their communities, while white Americans were forced to examine the realities of their democracy.