King: A Life—A Conversation with Jonathan Eig and Adam Green

In October of 2023 author Jonathan Eig and professor Adam Green joined Facing History for an event focused on understanding the humanity of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and how he spent his life challenging our democracy to live up to its promise of equality. Facing History Chicago’s Executive Director, Maureen Loughnane, led a conversation between these two academic writers as they discussed Eig’s most recent book, King: A Life. Together they considered the lessons we can learn today from King and other civil rights leaders.

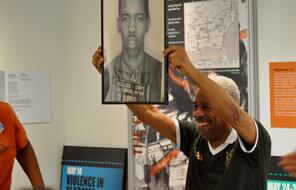

Professor Adam Green and author Jonathan Eig on stage in Chicago with Maureen Loughnane.

We asked our audience to listen to the discussion as if they were Facing History students—this was just another way to be a classroom community. Together we engaged with this discussion about history, identity, and the ways that choices shape our lives today and help us reach a more equitable future.

This excerpt from our conversation with Jonathan Eig and professor Adam Green can be a great entry point for new ways to teach about Martin Luther King Jr. and lesser explored stories around the civil rights movement and the people that spurred that pivotal moment in our country’s history.

Maureen: Jonathan, one of the many things I loved about your book was how you strive to bring to light Dr. King's many identities and his full humanity, including his faults. For those who have not yet read the book, King: A Life, can you share a few examples of this, and can you both share why demystifying Dr. King is so important today?

Jonathan: King had many roles. He was a teacher. He was a writer. He was a protest leader. He was an organizer. But when asked, he always said, ultimately, I'm a pastor—my job is to pastor to the nation. But he didn't seek to pastor to the nation. He was seeking really just a pastor to a congregation, as his father did and his grandfather had done.

Adam: One of many accolades I'm going to say in terms of Jonathan's wonderful book is that I think it conveys a sense of the experience of working for social change. And that's an experience that's uplifting, inspiring, and sustaining. But it can also be an experience that's difficult. And I think that one of the things that the book so powerfully conveys is King struggling in real time to make sense of how he can meet the demands of his historical and moral roles through what was, in fact, a short life.

This is a great lesson to all of us as we try to participate in change, because sustaining change and leading change is often hard. Recognizing that historical figures like King wrestle with many of the same challenges that many of us do in terms of trying to make a difference in our lives reminds us that our efforts count and that we can actually grow into the roles that we want to occupy.

Jonathan: I'm glad you said that, Adam, because it struck me that King seemed sad a lot. It struck me that his life was really hard, and it only got harder as he became more famous and more successful because the pressures on him were greater. All of his successes, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, did not mean that suddenly he could take the easy way out. In fact, he felt like he had to do more.

When he won the Nobel Peace Prize, it was Coretta who actually said to him, “We have a greater responsibility than ever now to speak out on a broader range of issues.” So King felt like he had to do more and more. And it didn't make him feel more powerful. He wasn't a politician who clamored for power. He was trying to do the morally right thing, and it just got harder and harder because his abilities were greater and the demands were greater.

Adam: The degree to which people tried to stand in the way of that change also grew greater.

Many King scholars have emphasized, for instance, the role of the FBI surveilling King throughout much of his life in terms of harassing to the point of sending inflammatory and incendiary letters to his wife and home in order to create discord and a disincentive to participate in this work.

One detail from the book that I felt was so powerful was that days after the March on Washington and the “I Have a Dream” speech—that was when the actual approval was given to tap King's home and office phones of SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference). And what that says is that there were elements in the government, notably J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI, but with the tacit approval of others in the government, who wanted to thwart King's work, and maybe even destroy the person. But I think it also reminds us that the kind of discord and challenges we see today—they existed in the 1950s and 60s. It reminds us that the lessons of how King navigated these divisions can help us navigate difficult conditions today.

Maureen: Building on that, I think there is an inherent tension in the telling of the history of social movements and certainly in the history of the civil rights movement between individual leaders like Dr. King and the other people who made up the movement. I am wondering how we should help young people to understand this tension as we teach about it?

Adam: There's that saying that someone who rises up stands on others’ shoulders. And we always have to remember that. One important point in the book is that I think of all of the people who have written about Martin Luther King, Jonathan did by far the best job of placing Coretta Scott King, his wife, at the center of the story. She's a frequent source. She often appears within chapters. Her voice is very prominent not only in terms of what she did to raise their children, to kind of maintain their home life, but how she functioned as a kind of counselor and advisor to King about how to maintain his moral commitment to the struggles that he had to take on as a leader.

Many wonderful contributions to uplifting the place of women within the civil rights movement have been made in the last generation of scholarship. But that choice to put Coretta Scott King at the center of a story about Martin Luther King, I think really reminded us that we have to think about who it is that sustains the people that we remember within history.

Jonathan: It's a really great question, Maureen, because often you'll see that biographies are criticized for focusing on one person—the great man approach to history—and I use man intentionally because all too often the women are left out. There's always the risk when you focus on one person, as I've done here with King, that you’ll neglect the broader portrait. And certainly the civil rights movement was the greatest grassroots movement in American history. There were many people who were involved and who were organizing in ways that King didn't. King was more of a beacon—he was shining a light on American racism, but others were much better at organizing.

In fact, Diane Nash was one of the few people who wouldn't talk to me for this book, and it was for that very reason. She said she's tired of all the focus on King because it comes at the cost of all of the other people who deserve some credit.

It's important to note that Martin Luther King, when he was first dating Coretta, had no history of activism. She had the far greater resume, and I think that's what attracted Martin to Coretta. She'd been to Antioch College where she'd been involved in protests on campus. The school would not allow Black students to student teach at white schools, and Coretta was fighting that actively. She attended the Progressive Party National Convention. She was already beginning to think about global issues of race and colonialism.

When she met Martin Luther King Jr., she was the superior when it came to activism. And I think that she knew that all along, and she knew that her job was not just to stay home and support the family, but to push him and to guide him. Of course, it didn't really help him overcome some of his own biases. He never really turned her loose the way she wanted because he believed that her role was to stay home and raise the children. So even some of our greatest fighters for justice have their own blind spots when it comes to justice.

But nevertheless, I think Coretta and many other women in the movement played crucial roles. You don't have a Montgomery bus boycott without the women who organized that community, long before Martin Luther King ever even moved to Montgomery.

Maureen: So now across our country, there are laws against teaching critical race theory, and there are threats of book bans. And these things have really had a chilling effect on the teaching of African American History. In light of that, I am wondering if you could both talk a little bit about the opportunities that teaching about Dr. King can present for educators.

Jonathan: I was just at Morehouse [College] a couple of weeks ago talking to students there, and we were talking about this very same issue. And we were talking about the possibility that Martin Luther King might actually be a secret weapon that we could use in this way because he is not just permitted in schools—he's required in many schools. Often the curriculum focuses on the safest, simplest, most comfortable versions of the King's story. But now that he's in there, maybe we can use him. Maybe we can start teaching the first half of the “I Have a Dream” speech—we only teach the second half. Maybe we can start teaching his “Beyond Vietnam” speech, which is, to me, his greatest speech because it talks about the moral rot that militarism does to all of our souls.

Adam: There's always an advantage of having a national holiday to make sure that you can't shut down conversation and learning about a figure. I think that one has to continue to identify the stories, the figures, the points at which people are compelled to listen in order to say that suppression of thought about these questions is something that's detrimental to society.

One thing that struck me in the book in relation to this question is how important it is to have appreciation for the full context of American history and African American history, and the history of social activism and social change, in order to understand who King was, what he was trying to do, what he was challenged by, in what ways he succeeded, and what ways there's work still to be done.

Jonathan was able to track down that Rosa Parks, four days before the bus boycott, went to a lecture by a gentleman named T.R.M. Howard who was from Mound Bayou, Mississippi, and he was the head of an organization called the Regional Council of Negro Leadership. This is 1955 in November, three months after Emmett Till had been lynched, but also several months after there had been seven or eight killings of African American activists trying to create conditions to vote and conditions of economic empowerment.

If we don't teach the full scope of African American History in our schools, we won't know who T.R.M. Howard is. We won't know who Rosa Parks is. We won't know who A. Philip Randolph is, who put together the movement to create the first March on Washington, and on and on in terms of thinking about this wonderful story that draws these different figures together that sustained King. It would be as if we blanked out all of that history, all of those influences, and simply put a single individual on a pedestal. We'll have no sense of context. And so I feel, to some degree as a historian, that it's important to say the story of the person is always the story of the whole community. And we have to know the whole community's history in order to understand the person.

Jonathan: When Martin Luther King is asked to speak during the Montgomery bus boycott, he's not the leader of anything yet. He's trying to avoid getting involved. He's 26 years old. He's got a two week old baby at home. He just said no to the NAACP when asked to join their Alabama board, but he gets up there because no one else really has the guts to stand up and to speak to the crowd. And what does up there is call for a revolution of values. He says it may be that we, the Black people of America, the people who have been treated the worst by this country, are the ones who can teach Americans how to really fulfill the promise of democracy. And he takes away the fear and fills the people in that room with a sense of pride that we can do something.

Fear was used to control people for so long. And Martin Luther King, inspired by Rosa Parks, who's inspired by the murder of Emmett Till, who was inspired by Howard's visit to Montgomery, is saying we're not going to be afraid anymore. Instead we are going to creatively fight. We can't fight back with weapons. We'll never win. But we can use the Bible. We can use the Constitution. We can show our moral superiority to those who are oppressing us. And in doing so, we will take away their superiority. We will take away their greatest power by not respecting it.