Monuments and Memorials Are Conversation Starters

Acknowledging history and grappling with how it affects our lives today are core lessons at Facing History & Ourselves. The rigorous study of history relies on a multitude of components. Among the most important are primary sources including texts, images, interviews, and objects from their time of origin.

Structures built to remind us of past events, significant people, or to honor the dead—monuments and memorials—can be primary sources. They can also be contemporary reflections of history. Old or new, monuments and memorials are a part of our historical accounting, offering a tangible medium with which to engage with our collective past.

Of course, monuments and memorials are subjective art pieces. They do not represent an entire history or all memories, but rather one perspective or story. But these perspectives and stories are pieces of the puzzle, giving us all a view into certain recollections of history, while also prompting big questions around who is memorialized and whose contributions are overlooked.

Dimitry Anselme, Facing History’s Executive Program Director for Professional Learning and Support, recently chatted with me about how monuments and memorials within classroom learning support dialogue, prompting students to seek out the bigger history behind a given single representational structure.

Jessica: What do you think the main purposes of monuments and memorials are?

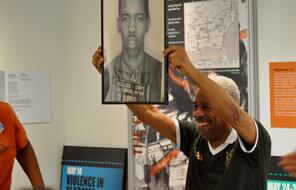

Dimitry: So, in order to answer that question, let me give you a little framing about how we think of memorials and historical legacies at Facing History. We do a session that is embedded in Holocaust and Human Behavior within the workshops and seminars that teachers attend. We even have teachers make monuments about what they're learning.

There are a couple of essential questions that we ask teachers to think about as they do this exercise that are very appropriate to consider around Memorial Day: How do nations choose to remember their history? And which story and whose story is told through the memorials that nations choose to have?

There’s a competition of memory. It’s important when at a memorial or monument to think about what the designers chose to remember and chose to leave out. And then whose stories come out of these monuments?

Jessica: In what ways do you think monuments and memorials play into either the history of Memorial Day or our current commemorations of Memorial Day?

Dimitry: The questions to always ask are who and what is being remembered, how is the story being told, and are there elements of the story that are being left out? That framework can apply to Memorial Day and many holidays.

When parts of stories are being left out in the monuments or memorials we see, I think we should move away from the language of correcting and judgment in the history classroom. As an exercise for Memorial Day or another commemoration, I would choose one monument to study and ask students: what is the common narrative around this monument? Do they think anything is being left out? Which voices are not represented by this monument?

Then once there is discussion of which voices are missing, a teacher can introduce those voices. For Memorial Day we might be highlighting a war or a group of soldiers. And I would ask students, “Okay, have you heard from the families of the soldiers? What do we know about the lives and perspectives of each individual who chose to serve? Why did they choose to serve? Have you heard from the people on the other side of that war experience?”

This is the point where historical primary texts can be used to give students access to more narratives. Students may be tasked with doing more research and digging for more specific information and stories.

Jessica: How do we grapple with monuments and memorials to people like our Founding Fathers, many of whom were slave owners?

Dimitry: So yes, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and others gave us an amazing set of documents. These were wealthy white men, landowners, some of them slaveholders, but also at the same time they proposed radical ideas about democracy and the equality of man—they weren't thinking about Black folks and women—but these ideas about freedom and equality prevailed and our ancestors have continued to use these documents and principles to expand rights to other groups.

I want students to recognize that, yes, these were affluent men and some slaveholders. But they are a part of our country’s history and they articulated a set of ideas that others took, broadened, and made open to all Americans. There is a tension there but it does not mean we reject these democratic principles. No, we commit to them even more because we recognize human frailty and that we are all flawed. This is not an effort at human perfection. It is an effort of striving for a more perfect union

Upstanders like Frederick Douglas or Elizabeth Caddy Stanton were not rejecting the Constitution or the Declaration of Independence because the narrative didn’t include them. They used these documents to make their arguments about expanding rights—they urged Americans to live up to the ideals captured in our founding documents.

Jessica: Now that people are more aware of the controversy they can cause, how do you think monuments and memorials will look or change in the future?

Dimitry: I've seen a couple of things that I love. In the beginning of 2001 we—the organization Facing History & Ourselves—did a civil rights learning trip for our Board members in Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

We went into these southern cities and small towns, and we noticed Black and white communities weren’t really talking to one another but instead were engaging in a competition of memory. So if the white community put up a statue, the neighboring Black community would then put up a statue too. We kept seeing this competition for memorials: the argument was, “Well, if you're gonna give money to put up X monument, we want money to put up Y monument.”

I do wish the communities would talk to one another as well. It would be really rich if we could do this monument-building in dialogue, because it's a way to begin to tell stories. From a student perspective, you will see and learn from both sets of monuments and understand the push and pull from both communities. Rather than seeing them in opposition, we would highlight the dialogue, the story they are trying to tell.

Another growing effort, which we borrowed from the Europeans, especially from Holocaust memorials in Germany, are public markers of our history. For example, Black artists who go into public spaces that were previously used as a slave market market, and they intentionally create something to interrupt your walk. It might be a tree or a block or something that forces you to stop and tells you, “Hey, did you know there is a larger history in this very physical space that you are now interacting with?”

I think that's incredibly powerful, and I would want to see us do more of that.

Jessica: This reminds me of the New England Holocaust Memorial that Facing History supported. It's not the same thing, because the Holocaust didn't happen in Boston, but I love that it’s near Quincy Market and integrated into the landscape near bars, restaurants, and other tourist attractions. You don’t necessarily know what you’re about to walk by, and then there just appears this beautiful, very sad, and really impactful memorial. It seems like a really great way to bring Holocaust memories and stories to people who might not otherwise seek out that kind of history.

Dimitry: I agree with you. That memorial is beautiful. I encountered it exactly in that way, too, not realizing I was about to come across this meaningful spot. I was very young. I wasn't even working at Facing History yet. I was a young immigrant and I happened to be in that neighborhood at night, and I was like, “Oh, what is this thing?” And then I realized, “Oh, my God, it's a memorial to the Holocaust.”

Faneuil Hall is very near that monument and it also has a history as a slave market. Historical records suggest that some Africans were being sold in slavery in there. But we have no monument about that. And before that the area of Faneuil Hall was also an Indigenous marketplace, because it was near the water. That's where Indigenous locals would come and meet to trade with each other and later with traders from Europe.

There is a way that we can highlight larger histories that are not actively told, and I look forward to future monuments doing a better job of that.

Jessica: How do you see Facing History's work on memory, legacy, and judgment being part of this conversation around monuments and memorials?

Dimitry: The idea of transitional justice is a concept that we have brought to Facing History’s work around memory. In the 1990s Facing History did a conference with Martha Minow when her book Between Vengeance and Forgiveness debuted. At the time there was this idea of transitional justice as we looked at countries who were on the path to building democracies: South Africa, Northern Ireland, Kenya, Chile. They were coming out of violent pasts and trying to create democratic societies.

So the space in which these emerging democracies existed was between vengeance and forgiveness. We talk to kids about nations and individuals being between vengeance and forgiveness. That in-between space is education. We discuss how you can get to a place where you recognize what you or I have done wrong, and then you could ask for forgiveness.

The other thing we've brought into the classroom is dialogue about memories. This includes learning how to read memories and stories. How does society contribute to memorials? And how do we get students to think about memorials while considering all the other voices that are not present or represented?

Earlier I mentioned the competition of memory and memorials. Facing History has also done a lot of work on memory. But memory is not history. We all have memories, so that's why we work with survivors. We work with survivors who came out of very violent moments in history. These are individual recollections, individual ways of telling stories. They are fragments. There is remembrance, but there are also things they choose to leave out because they want to protect us from the harshest parts. There are things people have chosen to forget.

So memory is not history, and we want teachers and students to remember that when they are interacting with memorials. When you are at a memorial or monument, you are exploring stories and memory—something that's not a complete picture or history. And even history is just a more disciplined or scientific way to capture a multiplicity of experiences.