The Power of a Single Word: The 75th Anniversary of the Genocide Convention

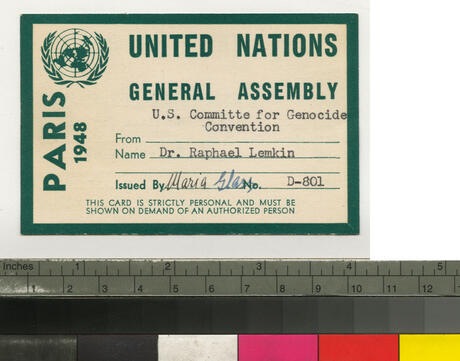

As the United Nations commemorates the 75th Anniversary of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the words of Raphael Lemkin, which created the foundation for that convention, continue to “strike at our consciousness.” His legacy has shown and continues to show that Lemkin’s and the Genocide Convention’s visions remain “a living force in world society.”

Lemkin’s vision calls on the world to answer the questions of who am I, who are you, and who are we. Only through an examination of those responses can we begin to define who we are as individuals, and who we are as a society. This approach also forces a global community to look at the consequences of defining membership based on perceived notions of race, religion, and nation. While countries and governing bodies have used the guise of membership to isolate, remove power from, and commit atrocities long before 1948, the events surrounding the Holocaust demanded a response like no other moment in history. International leaders were faced with decisions of how to punish those responsible for the systematic murder of over 12 million people and prevent a similar event from happening again.

Quickly it was realized that there was an even more fundamental problem to solve than the legal questions. The crime that had been committed had no name. This dilemma is where one of the most essential contributions of the Convention may be seen. The creation of the language to define a crime that, up until that moment, was “without a name” cannot be overlooked. Common language is crucial in a global community. While words or definitions cannot begin to explain the lives lost, the suffering experienced, or even what specific actions define this crime, it can and does lead to language that may educate and “strike at our consciousness.” And so it was determined that the crime of genocide would no longer be nameless.

The legacy of the Convention forces nation states to examine human conscience, human behavior, responsibilities, and how community membership is defined. Lemkin wrote about what he referred to as a “common destiny”––that some crimes could harm the world community as a whole; that these crimes were and are so horrific that they violate not only the laws protecting the individuals of a specific nation state, but also the principles shared as human beings. On December 9, 1948, the delegates of the convention voted yes to Lemkin’s vision to which he responded, “The world was smiling and approving, and I only had one word in answer to all of that. . . Thanks.” This moment was a rare one focused on international unity and human rights.

Aside from defining the crime of genocide, the 1948 Convention also provided language to attempt to hold those responsible for the crime accountable in an international court. Close to 50 years after the Convention, the first conviction for the crime of genocide was issued, and it was the first time the court defined rape as an international crime showing that the 1948 Convention was indeed a “living force” as it continued to expand the definition of genocide.

However, being a “living force” makes the continuous grappling of difficult questions a necessity. Can a society torn apart by war and genocide find healing and reconciliation? Who is responsible, and can they be held accountable? These questions extend beyond any one historical moment or its immediate aftermath by asking how to face this history to see if genocide, mass murder, and atrocities may be prevented.

While the questions may lead to an examination of history, they do not translate into action, to responsiveness, or to prevention. Challenges arise when state sovereignty and intervention are not aligned, when responses rely on individual voices, and when the definition of a global community is not uniform. The challenges continue to drive the necessity of the Genocide Convention to expand on this notion of being a “living force” moving beyond foundational language to be a core framework to educate the international community.

The legacy of the 1948 Convention encourages the definition of education to expand. Saying that education is the answer without exploring its goals and objectives is not enough. History has illustrated that educated leaders have been and can be responsible for allowing and promoting genocide. While there is no one lesson, strategy, or resource that will achieve all of this, one theme is evident. A historical analysis of past events is not enough. Students, teachers, and education systems must be able to make connections that provide ethical reflections allowing for informed civic agency showing that genocide prevention is a global issue regardless of the sector of work an individual is engaged in. Students that effectively take the academic approach required to strengthen international law, policy, and governance must also be provided an emotional connection that instills a necessity and a requirement to choose to participate in the active prevention of genocide.

When asked how to do this, Ben Ferencz, prosecutor of the Nuremberg Trials, often responded, “Law, not war” explaining that if this could be achieved everything could be changed. Ferencz would then respond, “Never give up.” This relentless perseverance needs to be at the core of any educational objectives centered around the emphasis of recognizing the humanity of others through the realization that people make choices and choices make history. Through the legacy of the 1948 Convention and the words of Raphael Lemkin, the foundational framework has been laid. The question remains, will a choice to face collective histories be made to not make genocide prevention a rare moment of international unity, but a shared vision of participation redefining the very essence of what it means to be in a global community? The choice is ours to make.

Image courtesy of the American Jewish Historical Society.