Universe of Obligation

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

9–12Duration

One 50-min class period- Culture & Identity

Overview

About this Lesson

In this lesson, students build on their previous discussion about stereotypes by examining why humans form groups and what it means to belong. This examination begins the second stage of the Facing History scope and sequence, “We & They.” Students will begin by reflecting on the different types of groups they belong to. Then they will read a poem and use it as an entry point for discussing the different ways people respond to human differences and the consequences of those different responses.

Once students have discussed their responses to the poem, they will turn their attention to their school or local community and, in a creative assignment, consider the ways in which they would like to see people respond to difference.

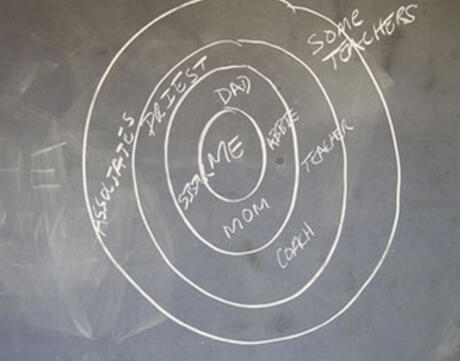

After reflecting on the ways people respond to difference, students will learn a new concept, “universe of obligation”—the term sociologist Helen Fein coined to describe the circle of individuals and groups within a society “toward whom obligations are owed, to whom rules apply, and whose injuries call for amends.” 1

Understanding the concept of universe of obligation provides important insights into the behavior of individuals, groups, and nations throughout history. It also helps students think more deeply about the benefits of being part of a society’s “in” group and the consequences of being part of an “out” group.

The activities in this lesson ask students to think about the people for whom they feel responsible. The activities also help students analyze the ways that their society designates who is worthy of respect and caring and who is not.

- 1Helen Fein, Accounting for Genocide (New York: Free Press, 1979), 4.

Preparing to Teach

A Note to Teachers

Before teaching this lesson, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plan

Day 1 Activities

Day 2 Activities

Assessment

Extension Activities

Materials and Downloads

Quick Downloads

Download the Files

Download allGet Files Via Google

Universe of Obligation

Stereotypes and “Single Stories”

Step 1: Introducing the Assessments

Unlimited Access to Learning. More Added Every Month.

Facing History & Ourselves is designed for educators who want to help students explore identity, think critically, grow emotionally, act ethically, and participate in civic life. It’s hard work, so we’ve developed some go-to professional learning opportunities to help you along the way.

Exploring ELA Text Selection with Julia Torres

On-Demand

Working for Justice, Equity and Civic Agency in Our Schools: A Conversation with Clint Smith

On-Demand

Centering Student Voices to Build Community and Agency

On-Demand