Building Support on the Home Front

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- The Holocaust

- Propaganda

Propaganda during World War I: An Appeal to You!

Propaganda is the use of information and media to influence public opinion. Propagandists during World War I relied on familiar stereotypes to evoke strong feelings like fear, pride, and prejudice, usually basing their efforts on facts that they embellished to demonize the enemy.

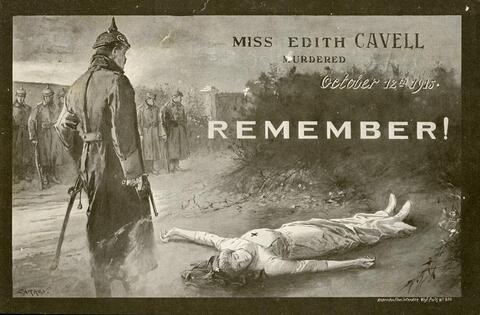

The postcard image that accompanies this reading was part of one of the most successful British propaganda campaigns during the war. It centered on Edith Cavell, a middle-aged British nurse who worked at a hospital in occupied Belgium. After the German invasion of Belgium, she joined an underground group that secretly aided Allied soldiers trapped behind enemy lines. When the Germans discovered her activities, she was arrested, tried, and found guilty of espionage. On October 12, 1915, the Germans executed her.

Edith Cavell Propaganda Poster

Edith Cavell Propaganda Poster

A British propaganda poster depicting the execution of Edith Cavell in 1915. Cavell was a British nurse working in Belgium during the German invasion. The Germans accused her of espionage.

In addition to building public support for the war, leaders believed it was necessary to forbid criticism and opposition. Official German policy, which was similar to policies in all fighting countries, suppressed expressions of anti-war sentiment by peace movements, pointing out especially the possible impact in other countries:

In the neutral countries as well as among our enemies, false impressions about Germany’s domestic strength will form. Every statement that can be interpreted as a sign of weakness or disunity is used by the enemy side, with obvious pleasure and satisfaction to energize the will and hope of defeating Germany militarily. Through personal contacts and correspondence, the impact abroad of these German apostles of peace can also cause immediate harm without their being aware of it themselves. Their statements about the domestic political, economic, and military situation can give the enemy important information, and it is to be expected that enemy agents will take advantage of the pacifist will to communicate . . . Finally, such behavior by people who portray themselves as representatives of German intellectual life is likely to diminish the respect for the German character and German diligence which we have achieved as a nation in arms. . . . It is thus necessary to make unambiguously clear to the people who stand out in the peace movement in an undesireable way that their activity is dangerous, and to put this communication somehow in writing. . . . Should they defy such a ban, they will have made themselves liable to prosecution. . . . The publication and distribution of pacifist writings and pamphlets may not be tolerated. Sending of these materials to foreign countries or to the front is to be prevented. Writings of this sort that arrive from abroad, as well as private letters whose purpose is to promote international pacifist goals, are to be confiscated. 1

Connection Questions

- Analyze the image of Edith Cavell above using the following process:

- First, look closely, observing shapes, colors, and the positions of people and objects.

- Second, write down what you observe without making any interpretation about what the image is trying to say.

- Third, list questions this image raises for you that you would need to have answered before you can interpret its meaning. Share and discuss your questions with another person, and try to find some answers.

- Finally, given the historical context you have learned, describe what you think the creator of this image is trying to say. Who is the intended audience, and what does the image’s creator want the audience to think and feel?

- Who tries to influence your ideas, opinions, and feelings today? How do they go about it? Which kinds of attempts to influence you would you classify as propaganda?

- Why would leaders believe that forbidding expressions of anti-war sentiment is necessary? Are there times during war or national crisis when the right of free expression and dissent must be suspended?

- 1“Suppression of Anti-War Sentiment (November 1915),” trans. Jeffrey Verhey and Roger Chickering, German History in Documents and Images website, German Historical Institute, accessed March 2, 2016.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Building Support on the Home Front," last updated November 6, 2017.