Western Front at the Cinema

At a Glance

Language

English — USSubject

- History

- Human & Civil Rights

- The Holocaust

Propaganda during World War I: An Appeal to You!

As the war dragged on, staggering casualties mounted. For example, at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, over 1 million men were killed in fighting between July and November, with little gain of territory by either side. Despite censorship, it was not possible to hide the death toll from the public. Leaders on both sides feared those huge losses might turn public opinion against the war. The British found a solution in a relatively new technology: the motion picture. Author Adam Hochschild describes its use:

Battle of the Somme Film

Battle of the Somme Film

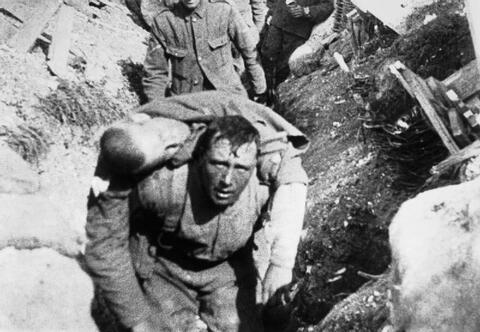

A still from the 1915 propaganda film The Battle of the Somme, showing a soldier rescuing a comrade under fire. Although the documentary included staged scenes, this frame was taken from a real combat scene.

Two cameramen with their cumbersome hand-cranked cameras were given unprecedented access to the front lines, and the resulting 76-minute Battle of the Somme was rushed into cinemas in August 1916, when the battle was not yet at its midpoint. It opened in 34 theatres in London alone, and 100 copies were soon circulating around the country. . . . In the first six weeks of its release more than 19 million people saw the film. . . . (Noticing its success, the Germans hurried out a copycat production of their own, With Our Heroes at Somme.)

For audiences accustomed only to short, set-piece newsreel clips of formal occasions like parades the film was nothing short of electrifying. Its black-and-white images also provided a wealth of detail about the front-line lives of ordinary, working-class soldiers, for here were the army versions of daily routines people at home knew so well—feeding and watering horses, preparing a meal over a fire, opening mail, washing up in a roadside pond, attending a church service in a muddy field—plus the drudgery of unloading and carrying endless heavy boxes of artillery ammunition.

Many parts of the film were calculated to inspire awe, such as shots of huge mines exploding underneath the German lines or the firing of heavy howitzers. TERRIFIC BOMBARDMENT OF GERMAN TRENCHES, says the title. Such scenes . . . are now believed to have been faked, taken well behind the lines, but neither audiences nor critics appeared to notice at the time, so riveted were they at what seemed to be the authentic nitty-gritty of the real war.

Millions of people must have watched The Battle of the Somme yearning for a glimpse of a familiar face—or dreading it; what if a husband or son appeared on the screen wounded or dead? For although the battle’s casualties were sometimes presented sentimentally . . . the remarkable thing is that they were presented at all. Unlike almost all earlier propaganda in this war, the film did not shy away from showing the British dead and surprising numbers of British wounded: walking, hobbling, being carried or wheeled on stretchers.

The film’s images, wrote the Star, “have stirred London more passionately than anything has stirred it since the war [began]. Everybody is talking about them. . . . It is evident that they have brought the war closer to us than it has ever been brought by the written word or by the photograph.” Men in the audience cheered when attacks were shown; women wept at the sight of the wounded; people screamed at the staged sequence showing British soldiers falling as if hit by bullets. . . .

The government had taken a calculated risk in allowing these images into the nation’s theaters. David Lloyd George, recently made secretary of state for war, argued that the film, however painful to watch, would reinforce civilian support for the war—and he was right. The more horrific the suffering, ran the chilling emotional logic of public opinion, the more noble the sacrifice the wounded and dead had made—the more worthwhile the goals must be for which they had given their all. 1

Connection Questions

- How did The Battle of the Somme portray the war? How did it appeal to viewers’ emotions? What was risky about showing this film so widely in Britain?

- War often provides its own justification. Once people have died for their country, why can it be hard for others to believe the war is a lost cause? Is it possible to honor the soldier but not the cause for which he or she fights?

- How do we distinguish between a film’s use to manipulate public opinion and its use to portray conditions as they truly exist?

- 1Adam Hochschild, To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914–1918 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), 227–28. Reproduced by permission from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company and Macmillan, London.

How to Cite This Reading

Facing History & Ourselves, "Western Front at the Cinema," last updated November 15, 2017.